Wheelchair Speed Governor

Sep - Dec 2022

This project was part of MIT mechanical engineering’s capstone class (2.009). I worked in a team with around 15 other people to develop a product intended to solve a real user need. Over the semester, we brainstormed ideas, interviewed users, and iterated on prototypes before demonstrating our product in the final presentation.

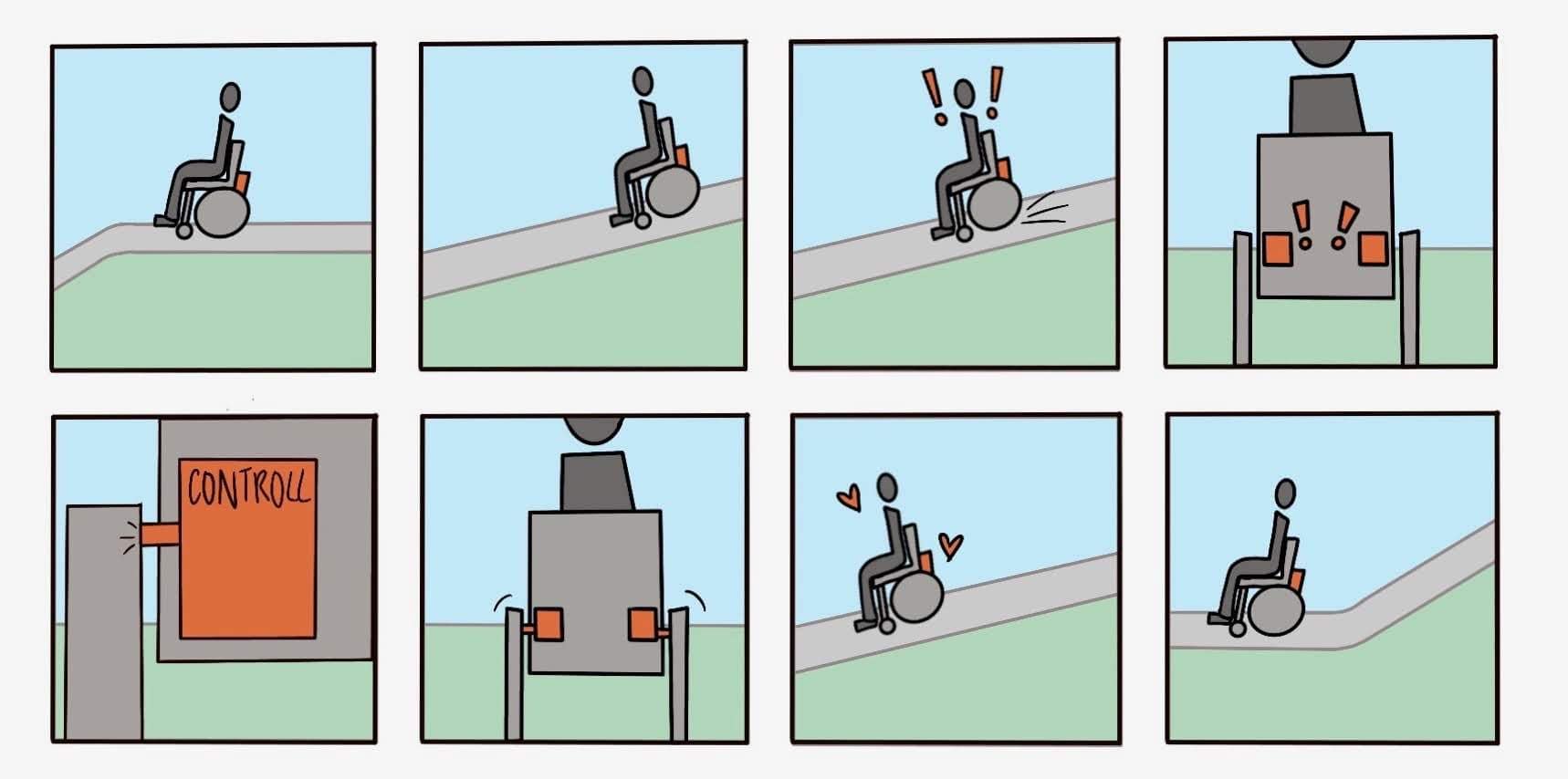

The idea we decided on was a device that automatically limits the speed of a wheelchair going down an incline. It also has the secondary purpose of protecting a wheelchair user’s hands since they would normally slide their hands on the hand rims to slow down.

One of the first problems we needed to solve was how to limit the speed of a wheelchair. I experimented with brushless motors whose leads were shorted out. However, I calculated that they wouldn’t provide nearly enough damping for the combined weight of a wheelchair and its user. Moreover, I knew from my interviews with wheelchair users that minimizing weight was a priority, and these motors weren’t particularly light. We also considered other strategies such as centrifugal clutches and shear thickening fluids but determined that they had too many tradeoffs (e.g., high weight, high energy loss when not in use).

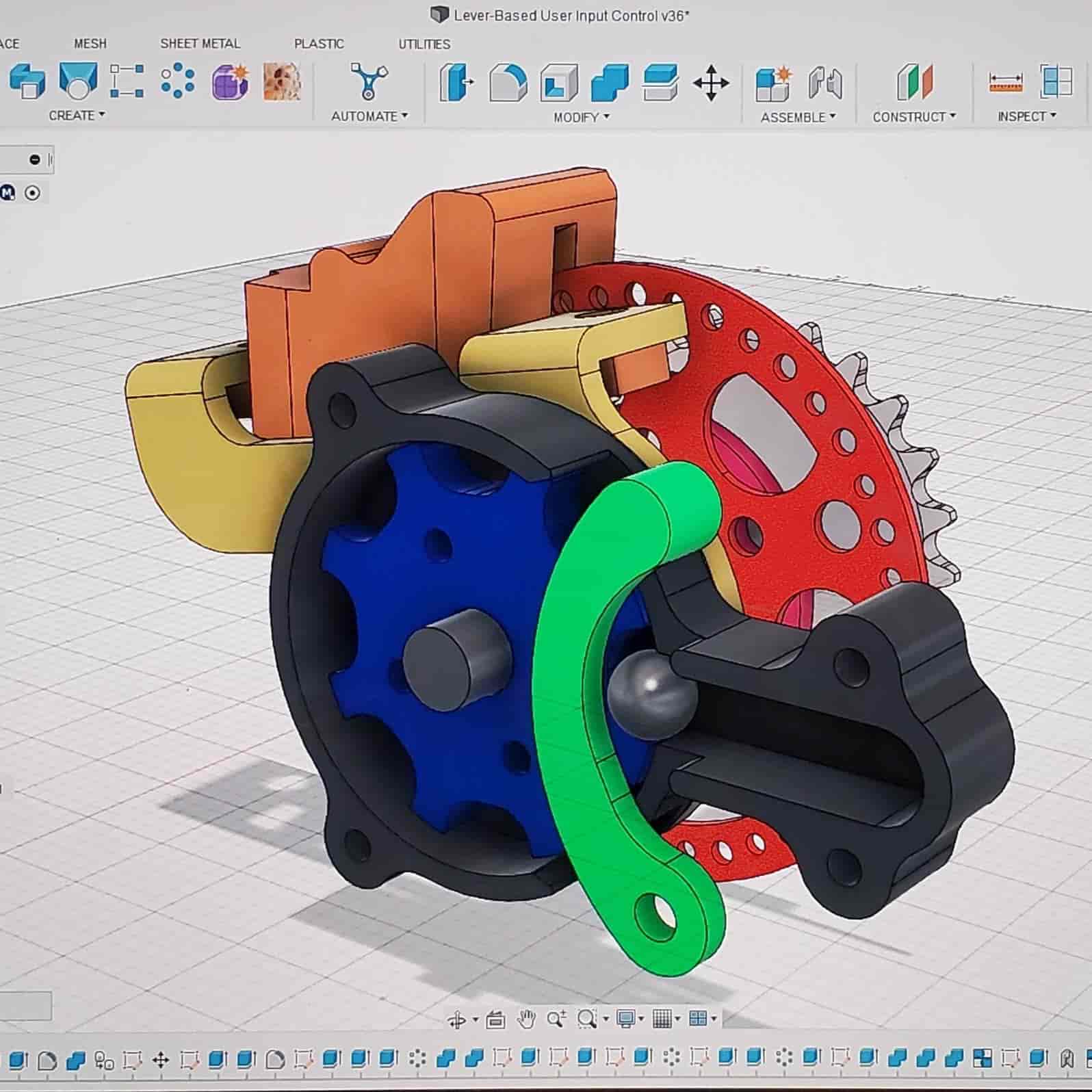

Eventually, we decided that bike brakes were the most practical way to slow a wheelchair down, but it was not clear to us how we would actuate them. In particular, we were unsure whether we wanted to actuate the brakes using an electromechanical solution or a purely mechanical solution. For this reason, we split into two subteams. I joined the mechanical subteam and proposed and prototyped the design shown in the video. The idea I had was to trigger the brake using the wheelchair’s tilt angle instead of the rotational speed of its wheel. In addition, instead of pushing brake pads against a brake disk, I proposed that we keep the brake pads preloaded against the brake disk and allow those brake pads to rotate with the brake disk. To actuate the brake, the device locks the brake pads to the frame of the wheelchair, which forces the brake disk to rub against the brake pads. The prototype in the video operates as follows:

- The black component is fixed to the wheelchair's frame.

- The white sprocket and red brake disk always rotate with the wheelchair wheel.

- The dark blue component holds a brake pad. When the wheelchair is not braking, the dark blue component and its brake pad rotate with the red brake disk.

- When the wheelchair tilts forward (such as when going down a ramp), a steel ball inside the black component rolls down and locks the light blue component against the black component.

- The light blue component rotates with the dark blue component. Therefore, when the ball rolls down, both the light blue component and dark blue component are locked against the black component.

- If the wheelchair wheel continues to spin, it forces the red brake disk to rub against the brake pad in the dark blue component. This should slow the wheelchair down.

This CAD screenshot illustrates the inner workings of the mechanism. This is the second version, but it uses the same operating principles as the first prototype. The main change was the green lever, which the user could rotate to switch the device between “always braking,” “tilt-activated braking,” and “never braking” modes.

In the end, my team chose to go with an electromechanical solution. This was because it was faster to implement, which was critical under our tight deadlines. Team members were also dissuaded by the fact that our subteam hadn’t tested a mechanical solution on a wheelchair yet. After this project pivot, I worked primarily on creating the animations for the final presentation and the housing of the prototype.

After creating multiple CAD mockups of the housing and listening to feedback from my teammates, I surface modeled this shape. I made sure to keep it symmetric so that the same design could be used on both sides of the wheelchair.

In the end, we had a working prototype that we were able to demonstrate onstage. What struck me the most was how much work went into things that no one outside the team would see. I have always seen this in large projects, but it seemed especially true in a large team project like this. My experience with the team also taught me valuable lessons such as how it’s more persuasive to communicate with physical prototypes and test results compared to ideas and CAD.